Naomi Feil was only 8 years old when she moved into what was then known as a nursing home, where her parents worked. Living there until she left for college, she learned firsthand, through trial and error, how to comfort and communicate with older adults.

When he died at age 91 on Dec. 24 at his home in Jasper, Oregon, he had dedicated his entire career to finding ways to comfort disoriented seniors and their caregivers.

His daughter Vicki de Klerk-Rubin said he died of cancer.

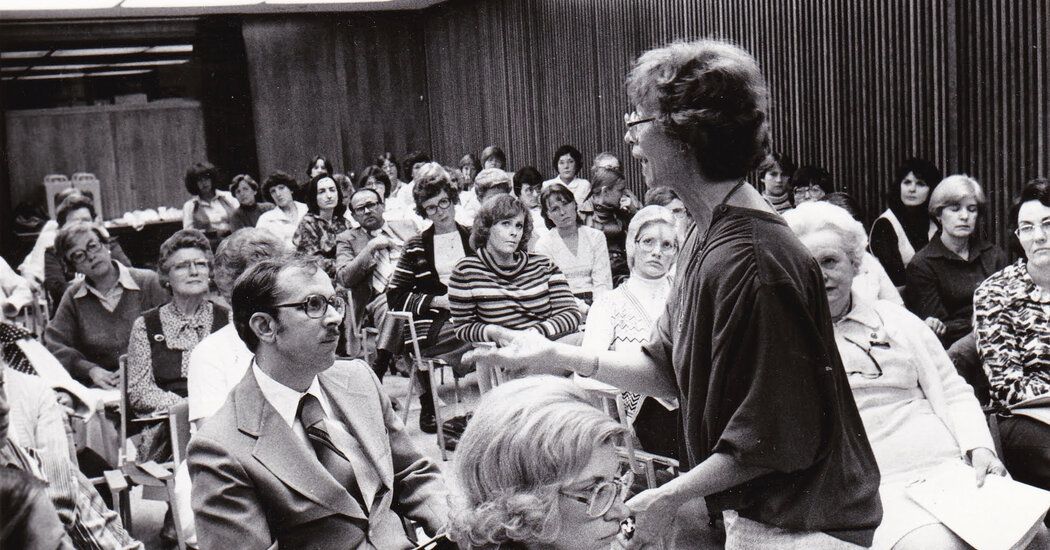

Ms. Feil was a 24-year-old social worker convening a group of patients diagnosed as “senile psychotics” when a staff psychologist at the Montefiore Nursing Home in Cleveland laid the foundation for what would become the method she called validation. therapy.

“He taught us that when feelings are 'validated,' they are relieved,” Ms. Feil explained on the website of her Validation Training Institute, a nonprofit organization in Pleasant Hill, Oregon. “'You are validating your residents, helping them release their pain.' When social work students asked me what I was doing, I responded, 'Validation.' And thus a new way of relating was formed.”

Their method requires caregivers to empathize with disoriented people in an effort to reduce their stress and support their dignity, rather than trying to impose reality on them.

“If you validate someone, you accept them where they are and where they are not,” Mrs. Feil (pronounced “feel”) used to say. “If you accept them, then they can accept themselves.”

While refining her methods, she founded the nonprofit Validation Training Institute in 1982. She ran it until 2014, when she was replaced by Ms. de Klerk-Rubin, her daughter.

“She was a pioneer in this area of person-centered dementia care,” Sam Fazio, senior director of quality care and psychosocial research at the Alzheimer's Association, said in a telephone interview. “The key to connecting with a person with cognitive impairment is to meet them in their reality instead of waiting for them to meet us in ours.”

His theory, like a related one called therapeutic deception, was not without criticism. The main objection is that it tolerates lying. The British Alzheimer's Society has said: “We struggle to see how systematically misleading someone with dementia can be part of a truly trusting relationship.” Others argue that lying or accepting a patient's illusion as reality is justified when it is in the patient's best interest.

There is still no consensus.

According to the Validation Training Institute, more than 9,000 people in 14 countries have been trained to communicate with people with declining cognitive abilities, especially dementia, by expressing empathy.

Ms. Feil wrote two books: “Validation: The Feil Method, Helping the Misguided Old Man” (1982) and “The Advancement of Validation” (1993). She collaborated on a later edition of “The Validation Breakthrough” with Ms. De Klerk-Rubin.

She and her husband, Edward R. Feil, a professional filmmaker, collaborated on several documentaries, including “The Inner World of Aphasia” (1968), which was included in the film registry of the United States National Film Preservation Board in 2015.

Gisela Noemi Weil was born on July 22, 1932 in Munich to Jewish parents. When she was 5 years old, her family had fled Nazi Germany to the United States, where her father, Julius Weil, became director of the Montefiore Nursing Home in Cleveland, and her mother, Helen ( Kahn) Weil, ran the home. department of social services.

After studying at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve University) in Cleveland, and earning her master's degree at Columbia University School of Social Work in New York in 1956, she married Warren J. Rubin. Her marriage ended in divorce.

He then moved to Cleveland and returned to Montefiore Home, this time as a member of the professional staff. She married Mr. Feil in 1963; She died in 2021.

In addition to Ms. de Klerk-Rubin, her daughter from her first marriage, Ms. Feil is survived by another daughter from that marriage, Beth Rubin; two sons from her second marriage, Edward G. Feil and Kenneth Jonathan Feil; six grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

She and Mr. Feil moved from Ohio to Eugene, Oregon, in 2015 to live on their son Edward's farm, where Mr. Feil, who suffered from cognitive decline, received full-time in-home nursing care, lessons piano, painting classes and validation therapy.

In the early 1960s, when she began working with disoriented people over 80, Mrs. Feil realized that helping them cope with reality was an unrealistic goal, one that would frustrate both caregiver and invalid.

“Each person was trapped in a world of their own fantasy,” he wrote in his first book.

“I learned validation from the people I worked with,” he added. “I learned that they have the wisdom to survive by returning to the past.”