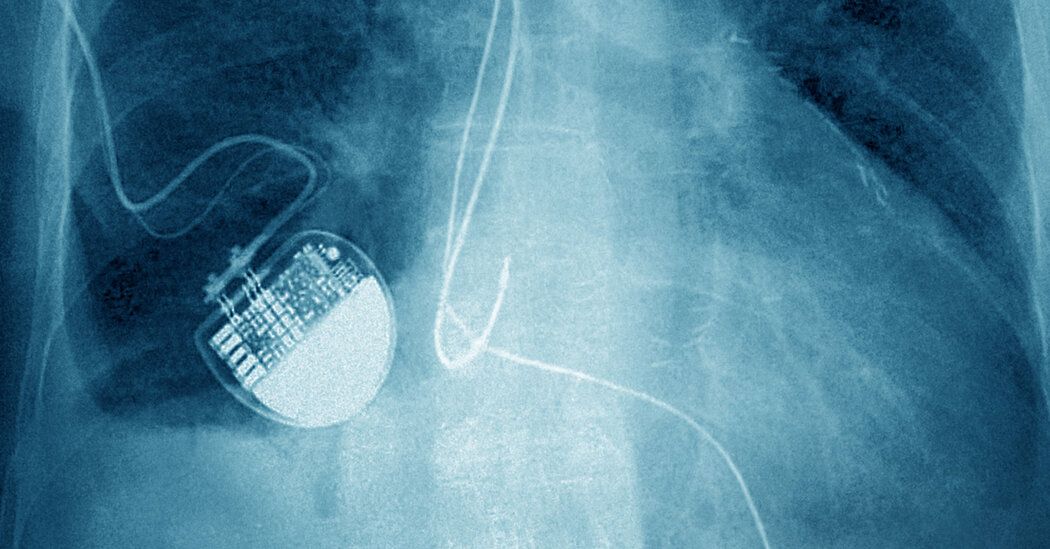

Like about three million Americans, Nancy Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of NBC News anchor Savannah Guthrie, has a pacemaker implanted in her chest.

Law enforcement officials investigating her abduction have reportedly contacted the company that manufactured Ms. Guthrie's device to find out what they can learn from the information it provides.

Experts in heart health and digital forensics say the answer may be “not much.”

A pacemaker constantly records a person's heart rate and uses that data to prevent it from dropping too low. If a person's lowest heart rate is set at 50, for example, the pacemaker will send painless electronic pulses when the rate drops to increase it again (unlike an implanted defibrillator, which shocks a stopped heart).

But while the device monitors a person's heart rate, a pacemaker “wouldn't help” find someone who has been kidnapped, said Dr. Michael Mack, a cardiac surgeon at Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas.

He and the other experts emphasized that they were not commenting directly on Nancy Guthrie.

Pacemakers constantly record data, but do not provide information about the patient's location, said Dr. Roderick Tung, director of the cardiac electrophysiology program at Banner University Medical Center Phoenix in Arizona.

A large majority of patients use remote monitoring, which involves a device that is typically placed on a nightstand. In some cases, this is an application on a smartphone. The monitor checks the data stored in the pacemaker throughout the day. Investigators did not say which company made Guthrie's device, or whether it uses that tracking method.

Dr. Kenneth Stein, global medical director at Boston Scientific, which makes pacemakers, explained that periodically, a remote monitoring instrument “wakes up” and transmits data, often at night when the patient is sleeping.

This data indicates whether the battery is in good condition and whether the pacemaker is working as it should. The device also transmits alerts if something is wrong with the patient's heart.

For pacemaker data to be sent to the monitor, the person must be nearby, typically no more than 10 feet away, Dr. Tung said.

Suppose someone is far from the monitor and that person's heart rate becomes erratic. Then, Dr. Tung said, that event would be stored in the pacemaker and transmitted only when the person approached the monitor.

It's like writing emails on a plane when there's no Wi-Fi, he explained. Emails are stored and then sent when you reconnect to the Internet.

Dr. Stein added that the reason the pacemaker only transmitted data occasionally was that the companies wanted to extend the device's battery life, which, in modern devices, is at least 10 years.

Data from the monitor is transmitted to the company, which then sends it to a doctor or clinic.

“There's a lot of cybersecurity to make sure it's protected,” Dr. Stein said, limiting the risk of a patient's private information being exposed.

He added that having the company analyze the data was similar to a lab testing company taking blood from a person, analyzing it and sending the results to the doctor.

Doctors check pacemaker data only occasionally, unless they receive an alert.

If a patient does not have remote monitoring, the doctor will see the data only when the patient comes in for a visit.

However, there is a way to learn something from a pacemaker after a person dies. Information from a pacemaker will show the time the heart stopped beating. It can reveal an event, such as a sudden, irregular heartbeat, that could have caused death. It can also indicate sudden death: a regular heart rate that then dropped to zero.

“It's like a black box on an airplane,” said Dr. Michael Lauer, a cardiologist and former deputy director of the National Institutes of Health.

A pacemaker ended up being a key help in solving a different mystery a year ago, when actor Gene Hackman and his wife, Betsy Arakawa, were found dead in their home near Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Since there were no witnesses, examination of Mr. Hackman's heart device allowed a pathologist to determine when the actor had died in the house, about a week after his wife's death.

Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs contributed reports.