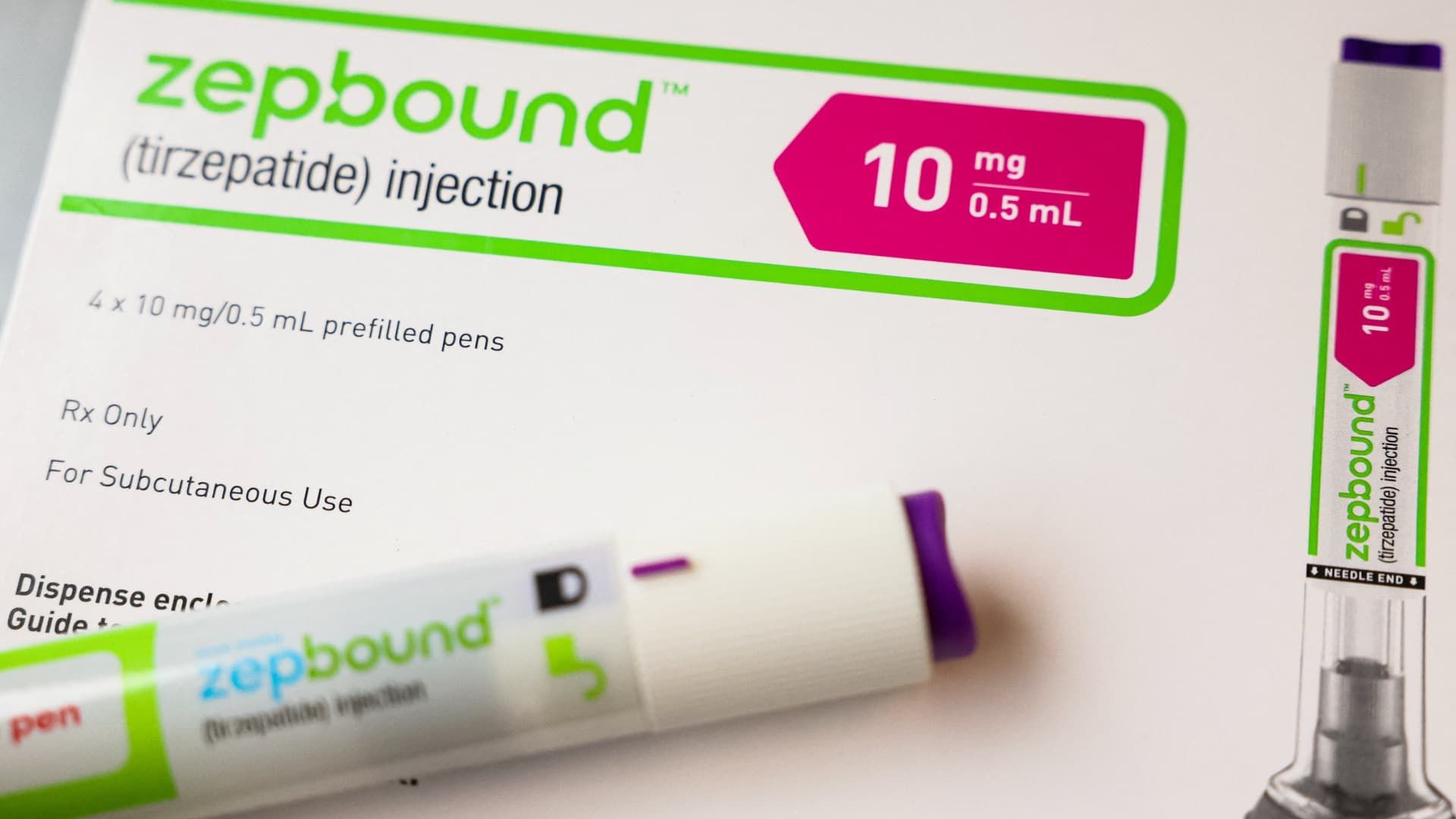

An injectable pen of Zepbound, Eli Lilly's weight loss drug, is on display in New York City on December 11, 2023.

Brendan McDermid | Reuters

The Food and Drug Administration said Thursday that the active ingredient in Eli Lilly The weight-loss drug Zepbound is no longer in short supply, a decision that will eventually prevent compounding pharmacies from producing cheaper, unbranded versions of the shot.

“The FDA has determined that the shortage of tirzepatide injectable products, which began in December 2022, is resolved,” the agency said in a letter. “The FDA continues to monitor supply and demand for these products.”

The agency's decision, based on a thorough analysis, marks the end of a period in which certain pharmacies were able to manufacture, distribute or dispense unapproved versions of tirzepatide (the active ingredient in Zepbound) without facing repercussions for status-related violations. of treatment shortage.

Compounding pharmacies must stop manufacturing compounded versions of tirzepatide in the next 60 to 90 days, depending on the type of facility, the agency said. The FDA said the transition period will give patients time to switch to the brand-name version.

It's a blow to some compounding pharmacies, which say their copycat drugs help patients who don't have insurance coverage for Zepbound and can't afford its steep price of about $1,000 a month. Zepbound and other weight-loss medications aren't covered by many insurance plans, but Mounjaro, Eli Lilly's diabetes counterpart, is.

It's the latest in a high-stakes dispute between compounding pharmacies and the FDA over shortages of tirzepatide, the active ingredient in both Zepbound and Eli Lilly's diabetes treatment Mounjaro. Eli Lilly has invested billions to expand its manufacturing capacity for tirzepatide as it struggles to keep pace with unprecedented demand.

A trade organization representing compounding pharmacies, the Outsourcing Facilities Association, sued the FDA on October 8 over the agency's decision to remove tirzepatide from its official drug shortage list just days earlier. The group alleges that the FDA acted without warning, ignoring evidence that a shortage of tirzepatide still exists. He also argued that the FDA's action was a blow to Eli Lilly that came at the expense of patients.

Following the lawsuit, the FDA said it would reevaluate removing tirzepatide from the shortage list. That allowed compounding pharmacies to continue making imitations while the agency reviewed its decision.

Compounded medications are personalized alternatives to brand-name medications designed to meet the needs of a specific patient. When a brand name drug is in short supply, compounding pharmacies may prepare copies of the drug if they meet certain requirements under federal law.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration does not review the safety and effectiveness of compounded products, and the agency has urged consumers to take approved brand-name GLP-1 medications when they are available.

However, the FDA inspects some outsourcing facilities that manufacture compounded drugs, according to its website.

Patients have turned to compounded versions of tirzepatide amid an intermittent shortage of brand-name drugs in the United States, which carry high prices of $1,000 a month before insurance and other reimbursements. Many health plans do not cover tirzepatide for weight loss, making compounded versions a more affordable alternative.

The active ingredient in Wegovy and Ozempic, semaglutide, has been in intermittent shortage for the past two years. But the FDA said earlier this month that all doses of those drugs are now available.

The agency has yet to announce whether it will remove semaglutide from its shortage list, a decision that would likely impact compounding pharmacies even more since it is more widely used than tirzepatide.

Wegovy, Ozempic, Zepbound and Mounjaro are under patent protection in the United States and abroad, and Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly do not supply the active ingredients of their medicines to outside groups. The companies say this raises questions about what some manufacturers sell and market to consumers.

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly stepped in to address illicit versions of their treatments, suing weight loss clinics, medical spas and compounding pharmacies across the United States over the past year. Last month, the FDA also said it had received reports of patients who overdosed on compounded semaglutide due to dosing errors, such as patients self-administering incorrect amounts of a treatment.