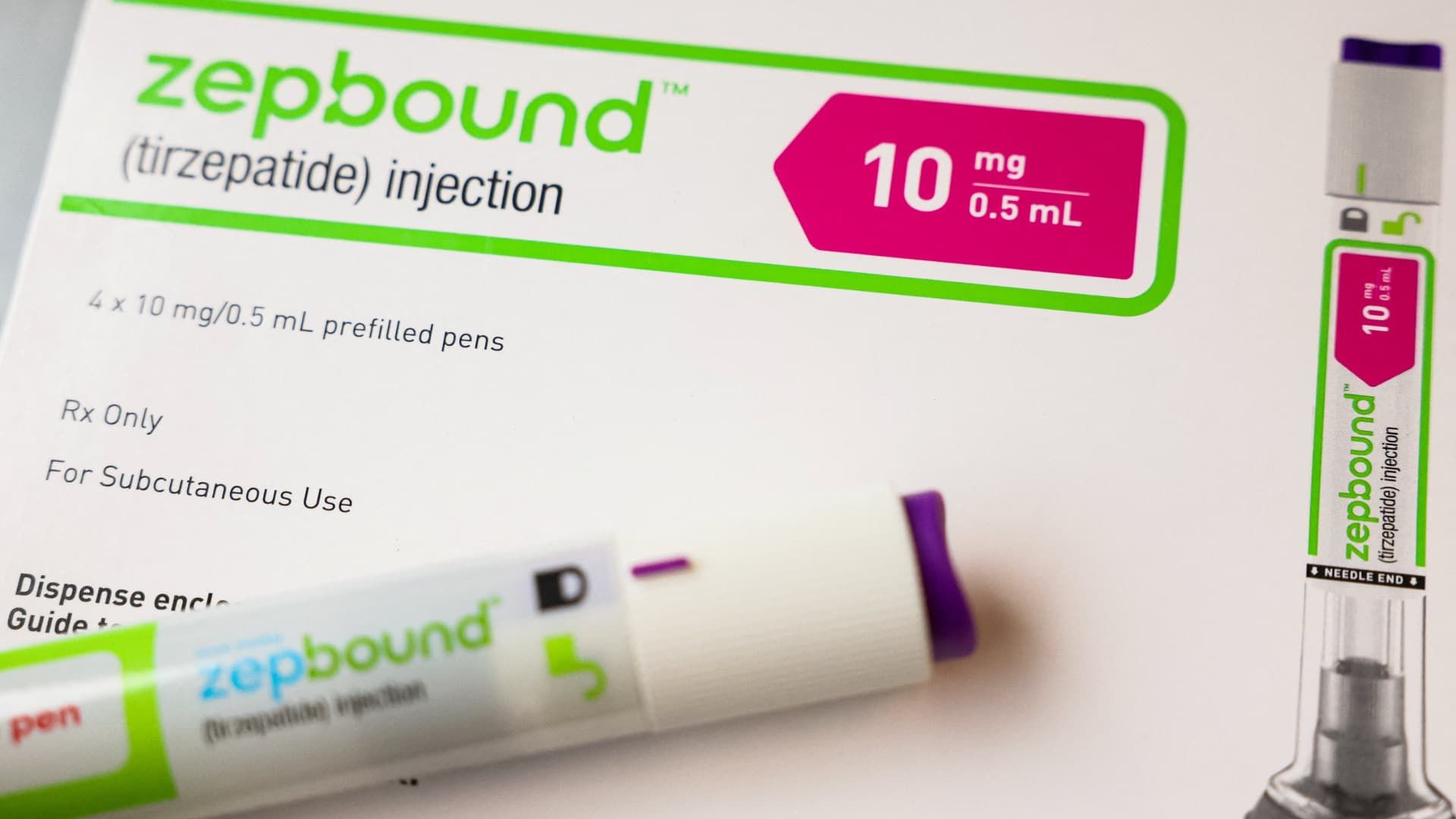

An Zepbound's injection pen, Eli Lilly's weight loss medication, is shown in New York City on December 11, 2023.

Brendan McDermid | Reuters

Eli Lilly It is demanding four telesalud companies that sell compound versions of the drug loss of the Zepbound pharmaceutical giant and its treatment of Mounjaro diabetes, the company's last attempt to take energetic measures against the booming industry of imitating medications.

In demands filed on Wednesday, Lilly accuses the sites (Mochi Health, Fella Health, Willow Health and Henry Meds, to deceive consumers about “drugs not approved and not approved” and move them away from Lilly's medicines.

Lilly alleges that companies claim to offer personalized options when in reality they are slightly different versions of Lilly's drugs to border the FDA rules. Lilly also states that some of the sites are selling drug formulations that have not been studied, as oral tablets and drops.

Fella, Willow and Henry Meds did not immediately respond to CNBC's requests. Mochi Health in a statement said that his model “continues to comply with the FDA orientation and pharmacy regulations.”

The medication of the diabetes of Lilly, Mounjaro, was scarce at the end of 2022, allowing pharmacies and subcontracting facilities to produce the treatment, a compound called. The drug loss drug Nordisk Wegovy was also scarce, opening the market to aggravate LPG-1.

That business rumbled online, where people were looking for versions of treatments if they couldn't find brands Or could not get them covered by insurance. The massive compound of Tirzepatida, the active ingredient in Mounjaro and Zepbound, was supposed to stop last month after the food and medication administration declared drug scarcity.

Some pharmacies continued to do it anyway, producing versions that differ slightly from the brand, which could possibly keep them out of the sight of the FDA. Earlier this month, Lilly demanded two pharmacies, claiming that they falsely marketed their products as personalized versions of the medications that have been tested clinically and are made using strict safety standards.

One of the Lilly Telesalud platforms is now demanding, Mochi Health, planned to continue selling versions composed of Tirzepatide, betting that offering personalized treatments would keep it out of legal problems, said the CEO of Mochi, Myra Ahmad, CNBC in March.

When asked if he feared Lilly legal actions, Ahmad said he was not worried about his prescribers, since “they have established patient medical relationships” and “the beauty of medicine is really that they get a complete autonomy to decide which is the best way to handle their patients.”

Lilly in his presentation on Wednesday said that Ahmad is not a licensed doctor and that Mochi and his “owners without a license exercise improper influence and control over, among other things, the prescription decisions of doctors” and, as a result, participate in the “illegal corporate practice of medicine.”

Ahmad in a statement said that the use of compound medications “remains appropriate and legal when it adapts to the individual needs of patients and prescribes a medical provider with a license” and that Mochi's doctors choose which treatments are the best for their patients. She said she has a Doctor of Medicine title but is not practicing as a CEO of Mochi.

Lilly makes a similar accusation against Fella Health, accusing the company of making “radical corporate decisions that dictate patient care, such as when Fella changed to mass patients from a Tirzepatide formulation to another with additives.”

In all four cases, Lilly seeks to prevent Marketen or sell Tirzepatide. But it could take months, or even more, that the cases break through the courts.