In early January in San Antonio, dozens of Ph.D. Economists crowded into a small, windowless room in the corners of a Grand Hyatt to hear new research on the hottest topic at their annual conference: how climate change is affecting everything.

The presentations in this session focused on the impact of natural disasters on mortgage risk, railway safety and even personal loans. Some attendees had to sit at the back, as the seats were already occupied. It was not an anomaly.

Nearly every block of time at the Allied Social Science Associations conference (a gathering of dozens of economics-adjacent academic organizations recognized by the American Economic Association) had multiple climate-related presentations to choose from, and most seemed equally popular .

For those who have long focused on environmental issues, the proliferation of climate-related articles was a welcome development. “It's very nice not to be the crazy ones in the room during the last session,” said Avis Devine, associate professor of real estate finance and sustainability at York University in Toronto, emerging from a lively discussion.

The conference, which is among the most important in the economics profession, tends to be a distillation of what the field is obsessed with at any given moment, and there is plenty of evidence that, after the hottest year in recorded history, the Climate is in the spotlight. .

There were articles on the local economic impact of wind turbine manufacturing, the stability of power grids as they absorb more renewable energy, the effect of electric vehicles on housing options, and how wildfire smoke affects finances of homes. Others looked at the benefits of a seawall for flood risk in Venice, the economic drag of uncertainty over climate policy, the flow of migrants displaced by extreme weather, how banks are exposed to emissions regulations and the impact of higher temperatures on factory productivity, just to name a few.

According to American Finance Association President Monika Piazzesi, half of the documents presented to her group were about environmental, social and governance investing, broadly defined, and there were not enough spaces to include them all. (Each association requests and selects its own papers to present at the conference.)

Janet Currie, incoming president of the American Economic Association, chose an environmental economist, Michael Greenstone of the University of Chicago, to deliver the conference keynote. It focused on the global challenge of moving to renewable energy and the corresponding potential to alleviate air pollution that is particularly deadly in developing countries such as India and Indonesia.

“This is not just a series of issues, but it is a large interrelated problem,” Dr. Currie said. “Not only economists but everyone else is realizing that this is a major problem and that it affects most people in some way. “That inspires everyone to want to work on it using their own particular lens.”

Or as Heather Boushey, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, put it while moderating a panel on the macroeconomics of climate change: “We are all climate economists now.”

It's not that the economy has ignored climate change. Research going back decades has predicted the toll warming will have on gross domestic product (an “externality,” in economics parlance) and extrapolated from there an estimate of how much a ton of carbon emissions should be taxed.

“There was a period when at least some people would think, 'Carbon is a non-internalized externality. We know how to address that,'” said Allan Hsiao, an assistant professor at Princeton University. They thought, “Maybe the issue is important,” he added, “but the economics and the underlying tensions, the subtle and not-so-obvious mechanisms, were not there.”

That perception has changed. A solution favored by economists, setting a cap on carbon emissions and creating a market for permit trading, failed in 2009 under the weight of a weak economy, administrative complexity and determined opposition. A different approach has emerged in recent years: providing incentives for clean energy production, which pays more attention to political realities and the equitable distribution of costs and benefits, two issues that have also attracted more attention in economic circles lately.

It has also created a collision of new questions, providing material for a bonanza of dissertation topics. “Now people are realizing that there is a lot of wealth,” Dr. Hsiao explained.

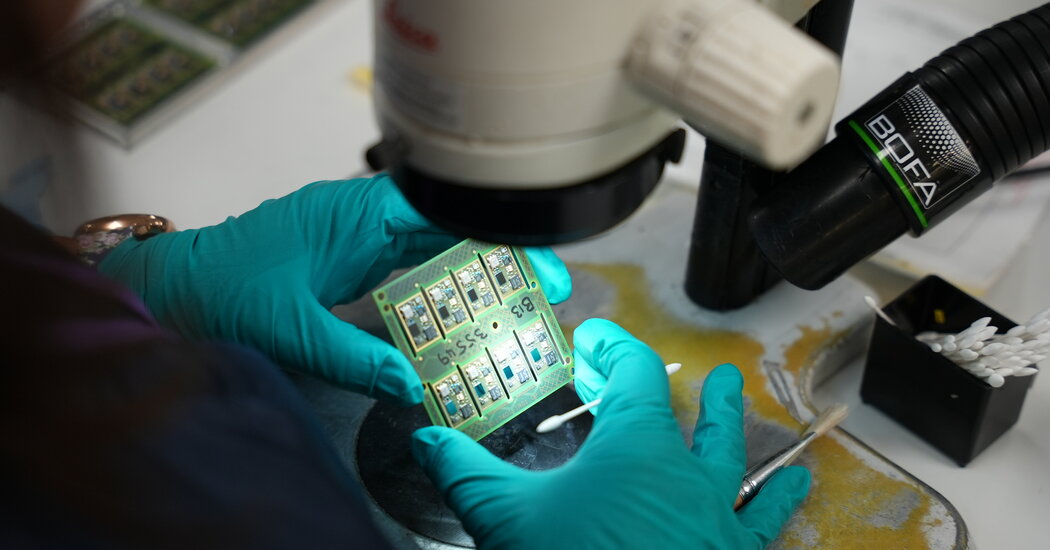

The rise of climate research in economics comes in part from established figures who are finding ways to address related questions as a branch of their own specialization. But much of the enthusiasm emanates from newcomers to the field who are only now building their publication records, learning how to wrangle the universe of geospatial data from sources like weather satellites, temperature sensors, and historical precipitation records.

Take Abigail Ostriker, who is doing a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard before starting as an assistant professor at Boston University this summer. She had become displeased with climate as an area of focus while in college during the 2010s, after the death of emissions trading legislation in Congress ushered in a relatively stagnant period for climate policy.

But he picked this up again in graduate school, realizing there was a lot of work to be done to figure out how societies can deal with the effects of climate change, now a new normal, not a distant threat.

“I felt like climate change was already here,” said Dr. Ostriker, who earned her degree with a paper on how floodplain regulation in Florida changed housing construction. “I've been focusing my attention on the adaptation side: where will we see these consequences and what policies will protect people from the consequences? Perhaps policies will exacerbate them in perverse ways?”

The emerging generation of climate economists is not only bringing new ideas and energy. Specialization is attracting more women and people of color to economics, helping to change the face of a field that has long been notoriously white and male, said Paulina Oliva, an associate professor at the University of Southern California who helped select papers for the American Economic Association Program at the San Antonio conference.

“For me, that's been particularly exciting, because you know how difficult it has been for the economy to have diversity,” Dr. Oliva said.

To attract young researchers to the field, it helps that demand for climate economists is booming—at colleges and universities, but also at government agencies, private companies, and nonprofit think tanks. A website that tracks job openings for academic economists around the world, EconJobMarket.org, shows that 5.5 percent of ads mentioned the phrase “climate change” in 2023. A decade earlier, that figure was 1.1 percent, said Joel Watson, a professor at the University. of California, San Diego, who manages the site.

Those opportunities include many in the U.S. government, which has been incorporating climate priorities across a variety of agencies since President Biden took office in 2021. Climate impacts are now part of the cost-benefit analysis of new regulations, are taken into account in economic growth projections and reflected. in budget forecasts.

The Inflation Reduction Act did not set a price on carbon, which economists had advocated for decades. But Noah Kaufman, a researcher at Columbia University's Center for Global Energy Policy, believes his tools could be guided by economic analysis to transform the energy system, while cushioning the impact for communities that depend on fossil fuel production. and guaranteeing the benefits of renewable energies. Energy investments are widely shared.

“Economists need to catch up with policymakers,” said Dr. Kaufman, who worked for a time on climate policy on Biden's Council of Economic Advisers. “It is unfortunate that we did not produce this literature decades ago. But since we didn't, it's very exciting and a unique opportunity to try to help now.”