Inside room 501 of the Sheraton Plaza La Reina Hotel near LAX, the trap awaited John DeLorean.

It was October 1982, and the maverick automaker had been losing money hand over fist. Ten years earlier, he had left a job at General Motors, where he was making $600,000 a year, to pursue a bold ambition to start his own car company. The result was a futuristic-looking, stainless-steel sports car with gull-wing doors, designed to compete with the Corvette.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, from the momentous to the obscure, delving into the archives and memories of those who were there.

But the project was plagued by quality control issues and the price tag, at $25,000, was too high. His dream was on the verge of collapse and his company was heading for bankruptcy.

He had flown to Los Angeles for this clandestine meeting. He entered the hotel room and sat among men who had told him about his underworld connections and had promised to help him.

DeLorean seemed to be in a very good mood. One of the men opened a suitcase full of cocaine and DeLorean looked inside.

DeLorean was an American original, the rare auto industry executive to achieve a high public profile. He exuded glamour. As a businessman, he was adept at developing personal brands years before Donald Trump, and a visionary automaker years before Elon Musk. Profile writers frequently described him as “dashing,” “flamboyant” and “dapper,” a “jetsetter” and a “daring.”

The son of a Ford foundry worker, he grew up in a working-class Detroit neighborhood and rose rapidly through the ranks at Chrysler, Packard and General Motors. In 1961, he became chief engineer of GM's Pontiac division and introduced two popular muscle cars, the GTO and the Firebird. By 1972, he was a GM vice president and was being talked about as a possible candidate for president.

DeLorean cars are lined up at the company's preparation facility in Santa Ana.

(Cliff Otto/Los Angeles Times)

But his outsized personality and extravagant lifestyle clashed with the company's formal culture. He wore scarves, bell-bottoms and open shirts. He had surgery on his chin. He grew sideburns. He hung out with stars.

At 48, he married his third wife, 22-year-old model Cristina Ferrare. They lived opulently in a Fifth Avenue apartment in New York and on a 430-acre estate in Bedminster, New Jersey. His cross-stitch pillow read: “Nouveau is better than not being Riche at all.”

In 1973, he left GM and set out to do what no one had done successfully since Walter Chrysler in the 1920s: start his own car company. His vision was to build an “ethical” sports car: safe, practical, rust-resistant and also “very aesthetically pleasing.” He persuaded the British government to invest more than $140 million in his project and opened a plant in Northern Ireland, which produced some 9,000 DMC-12s between 1980 and 1982.

Plagued by electrical problems, the car failed in the marketplace. The British government withdrew funding and, in early 1982, declared DeLorean Motor Co. insolvent.

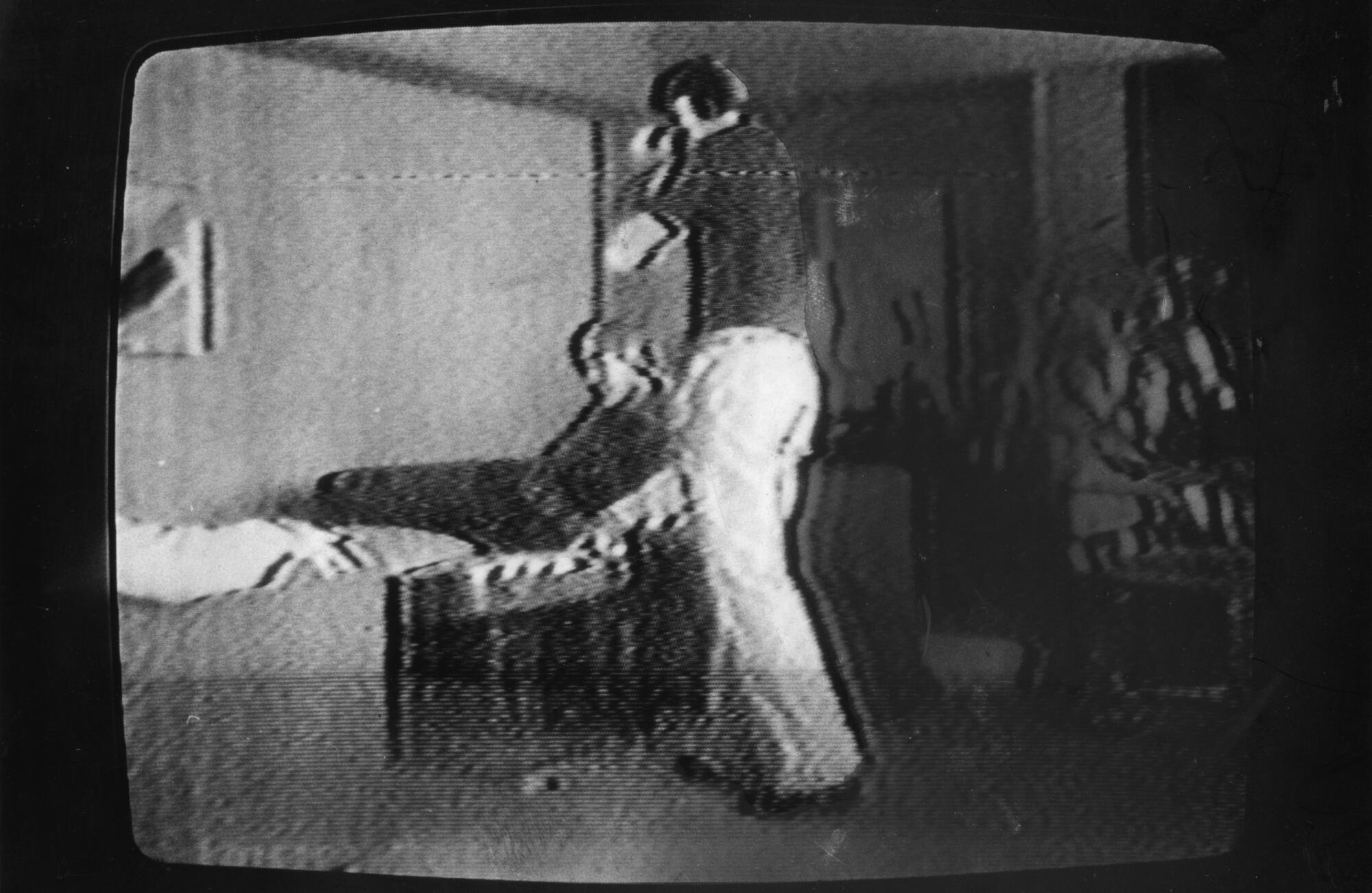

The men who met DeLorean at the Sheraton that day were federal agents and an informant. In blurry footage captured by an FBI hidden camera, DeLorean inspected the cocaine-filled suitcase and said, “It's better than gold.”

Toasting with a glass of champagne, he added: “Much success for everyone.”

Federal agents moved in to arrest him. The FBI alleged he was part of a scheme to buy and resell 220 pounds of cocaine from Colombia in a desperate attempt to save his business. The charges, which would carry a 67-year prison sentence if convicted, generated enormous publicity.

An FBI hidden camera caught John DeLorean examining a suitcase full of cocaine and calling it “better than gold.”

“He was a very famous guy. He had what seemed like a magical world,” Donald Re, one of his defense attorneys, told The Times in a recent interview. “It seems incredible that this guy would volunteer to do this kind of transaction. ‘Well, I guess rich people can do this kind of thing,’ that’s what people thought.”

Talk show host Phil Donahue gave some insight into the appeal of the case. “We love these kinds of stories,” he said. “The mighty have fallen.”

Central to DeLorean’s trial, which began in April 1984, was the credibility of the government’s star witness, James Hoffman, a convicted drug dealer and perjurer who was on the stand for 18 days. He had lived across the street from DeLorean’s home in San Diego County and had turned informant in hopes of gaining leniency. He said DeLorean proposed a drug deal to save his company.

For the defense, the government’s clandestine recordings were difficult to overcome. In one conversation recorded by federal agents, Hoffman told DeLorean: “Nobody wants you to do anything you’re not comfortable with.”

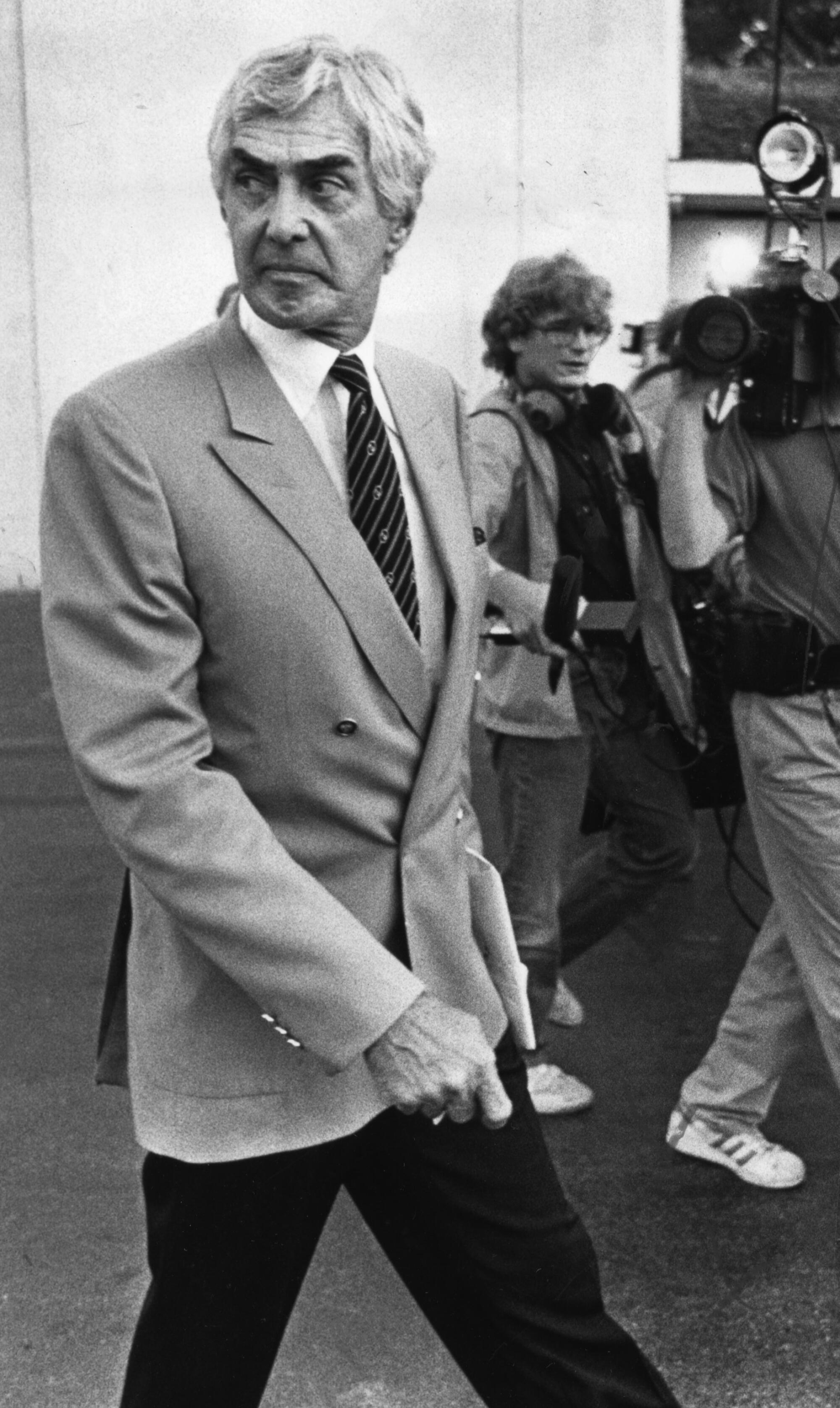

John DeLorean leaves the FBI office in Westwood after taking a lie detector test.

(Joe Kennedy/Los Angeles Times)

DeLorean said he wanted to move on, telling Hoffman: “I trust you’re going to tell me there’s no way I can relate to this.”

“You're not going to tamper with the product,” Hoffman said.

In a valiant defense, DeLorean's lawyers, Re and Howard Weitzman, took the government to court. They portrayed DeLorean as the victim of a manipulative whistleblower who had lured him with the prospect of legitimate investments in his company, later introducing the notion of a drug transaction.

“I'm going to get John DeLorean for you,” Hoffman said, according to testimony from a former DEA agent. “With the problems he has, I can make him do whatever I want.”

When DeLorean said he didn't have the money for the settlement, the agents should have abandoned the investigation, the defense claimed. Instead, they devised an elaborate funding scheme to keep him involved and manipulated footage of the operation.

Yes, DeLorean had acted with poor judgment, the defense argued, but he was simply looking for money to invest and had not committed any crime. Even if the jury decided that he had, it was a case of cheating.

“DeLorean was manipulated,” Re told jurors. “DeLorean was manipulated. DeLorean was defrauded. John DeLorean in this case was a victim, a victim of the people whose duty it was to protect him from criminal activity.”

In a recent interview, Re said DeLorean had been tricked into participating in the drug business and feared physical harm from underworld figures if he tried to get out. DeLorean did not contribute cash to the deal, Re added, but instead offered an equity stake in his company.

“This business was the highlight of his life,” Re said. “There was no way he would have been able to do it unless he felt like he was being forced into it, unless he felt like something horrible was going to happen to him.”

Federal agents display cocaine seized during the arrest of John DeLorean in Los Angeles in October 1982.

(Doug Pizac/Associated Press)

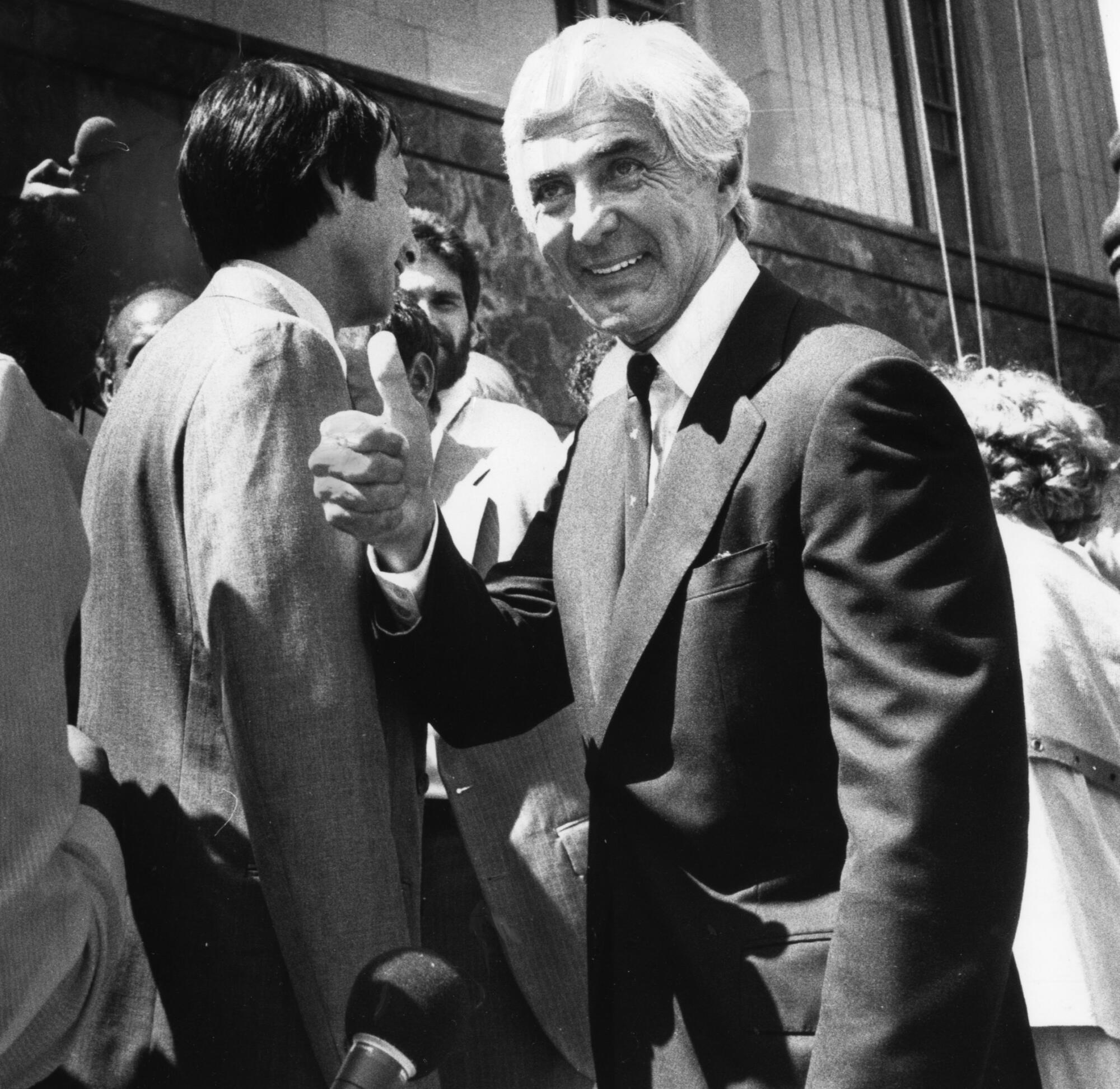

DeLorean, 59, never took the stand during the five-month trial. After 29 hours of deliberation, the jury acquitted him of all charges.

“The way the government agents acted in this case was not appropriate,” one juror said. Others said Hoffman lacked credibility. Some said DeLorean was morally, if not legally, culpable: “I don’t think he was ‘innocent.’ … He was ‘not guilty.’”

Federal authorities acknowledged a major strategic mistake: failing to ensure that DeLorean had provided its own money.

DeLorean said he had aged 600 years in the past two years. “My life as a hard-working industrialist has been shattered,” he told the media. “Would you buy me a used car?”

DeLorean's wife, who had been faithfully by his side throughout the ordeal, soon left him. In an interview a few years later, she said: “I think John is a sociopath.”

DeLorean converted to Christianity and told Playboy that he had fallen victim to his own “insatiable pride… an arrogance that surpassed that of any other human being alive.”

The trial was still fresh in memory when the DMC-12, equipped with the mysterious “flux capacitor,” served as a time machine in the 1985 hit “Back to the Future,” enshrining it in pop culture. DeLorean sent a glowing letter to the filmmakers, who were glad they hadn't gone with the original idea, a time-traveling refrigerator.

John DeLorean after his acquittal on drug charges in August 1984.

(Lori Shepler/Los Angeles Times)

In 1986, DeLorean won another federal case, this time in Detroit, accused of stealing $17.5 million from his investors. But he faced a huge amount of legal fees and creditors were stalking him.

He tried to market watches and talked of building a “radical new car.” His plans failed, and in 2000, vans came to his Bedminster estate to take away his antiques. He was living in a New Jersey apartment when he died in 2005, aged 80.

Times columnist Dan Neil called him “the last of the auto industry’s outsiders” and wrote, “DeLorean goes down in history not as a visionary but as an arrogant, amoral hipster, a victim of his own toxic vanity.” Weitzman, the attorney who successfully defended DeLorean, said that of his many clients, “John DeLorean had one of the most distorted views of right and wrong.”

Documentary filmmaker Tamir Ardon got close to the DeLorean family during the 15 years he spent bringing the 2019 documentary “Framing John DeLorean” to the screen. He called the cocaine case “Entrapment 101,” which unfolds against the backdrop of Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs.

“Morally, John was corrupt. Legally, he didn’t do anything wrong,” Ardon told The Times in a recent interview. “He wasn’t involved in drug trafficking. It just happened that that was how they structured the case to make it look super nefarious and be super eye-catching to Reagan. … They thought that as long as they got this eye-catching video of John in a room with cocaine, that would be damning enough for a group of 12 regular jurors.”

Ardon said there are still about 6,000 DMC-12s in circulation and that mint-condition ones can fetch a six-figure price. Depending on its age, people associate the car with either the “Back to the Future” franchise or the clinical trial. The dividing line is around 50 years.

“The most common question any DeLorean owner gets is, ‘Where’s your flux capacitor?’” Ardon said. “And the other is, ‘Where’s the cocaine hidden in your car?’”