In the City they have been shaking their heads. “That would never happen in Jacob's day.”

They refer to the trauma at St James's Place, Britain's biggest wealth manager, which has seen its shares plummet amid accusations of overcharging clients. The company has set aside £426m for potential refunds to aggrieved customers.

Bank of America analysts say this is the “culmination of an annus horribilis” for St James's, which is based in Cirencester and oversees £168.2bn for almost a million clients.

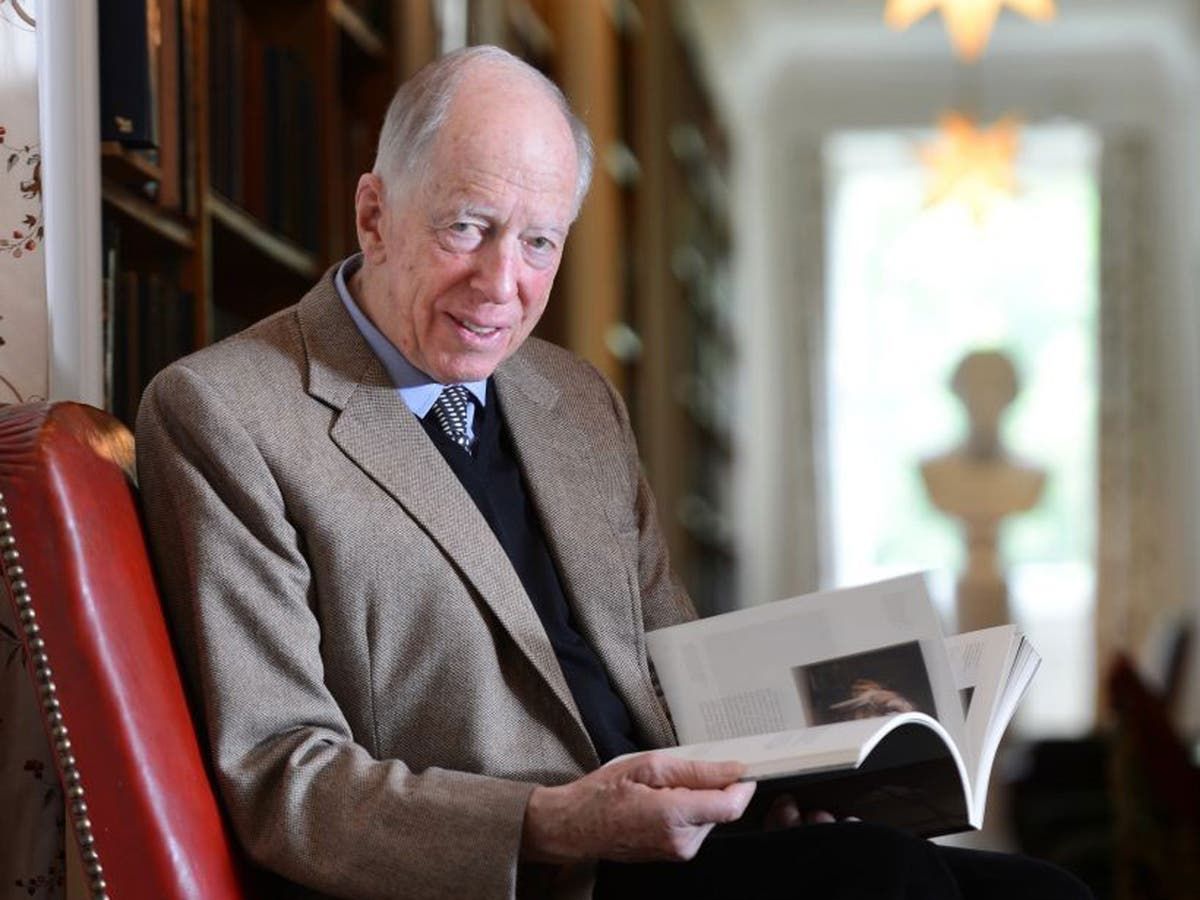

If this is the end, he may survive, but another major reputation problem could be enough to ruin him. Either way, the episode has made old-timers of the town remember St James's as it once was. They have also been prompted to do so by the death, coincidentally also this week, at the age of 87 of co-founder Jacob Rothschild.

Together with his late business partners Sir Mark Weinberg and Mike Wilson, Lord Rothschild founded St James's Place in 1997. The trio long ago ceased having any relationship with the company. The consensus is that they would not have let their company sink into such a disaster. In its time, St James's was built on discretion, care and rigorous analysis.

In recent years, the company has been hit by controversy and criticized for high-pressure sales tactics. Advisors received Montblanc pens, Mulberry bags and all-expense vacations. Never, back in Jacob's time.

It is a measure of Rothschild's stature that in the City he only requires introduction by his first name. Everyone knows who they are referring to.

He was an imposing figure. Tall, stooped, of impeccable manners and dress, blessed with a fiery intellect and a user of few words, Rothschild was someone who was always watched, always at the center of speculation, looking for any clue, a sign of things to come. to do next.

He was an astute judge of character, with the ability to detect weaknesses and an inquisitorial nature. A coffee with him was like being in a university tutorial again. Once I was with him when he asked my partner a rather long-winded question. Before he could respond, Jacob said, “Why don't you start with the ending?”

Rothschild instilled respect, fear and excitement in those he crossed paths with. A member of the banking dynasty of the same name, he discarded the silver spoon, broke away from the family bank and fell out with Evelyn de Rothschild, his director and cousin. Jacob created two highly successful financial powerhouses: investment trust RIT Capital and St James's Place.

But he was more than that. He was the last of the London buccaneers who stalked deals at home and abroad decades ago, orchestrating audacious takeover bids and striking spectacular deals. Along with James Hanson, Gordon White, Jimmy Goldsmith, Arnold Weinstock and Tiny Rowland, Jacob Rothschild would deliver surprise after surprise, taking the City by surprise and keeping the markets guessing. They followed the rules when required, but preferred, if they could, to follow their own.

Sometimes they were both friends and rivals, titans who treated the Square Mile and Wall Street as means to an end. In 1989, there was a stir with the sudden announcement of a press conference at the Hambros Bank headquarters. There were Rothschild, Goldsmith and the Australian tycoon Kerry Packer. They were going to buy BAT or British American Tobacco for £14 billion.

Without anyone realizing it, they had created a company called Hoylake. It would be your bargain vehicle. They had planned the deal at Simpsons in the Strand, in the Grill Room. They had reserved all the nearby tables so they couldn't hear them. BAT had no idea what was coming. His statement, describing the attack as “unsolicited and unwanted,” was hysterically understated; BAT was shaken to the core.

In the end, the trio's strike failed. But it wasn't for lack of trying. That was always the point for them: nothing was too big, too remote, if they wanted it and it met their criteria, they would try it.

Although it was a serious business, with exorbitant consulting costs and many hours of preparation, there was always a sporting element to what they did. They often applied the same enthusiasm and focus to other aspects of their lives, whether it was their fine art collection, racehorses, wine (when he died, Jacob had 15,000 bottles in his cellar), houses, or women.

Jacob, however, stood out. He was happily married to Serena for 58 years until her death in 2019. Together they transformed numerous properties, including his villa in Corfu, her house in Pewsey and Rothschild properties in Waddesdon and Eythrope and Spencer House. It was at the latter location that Rothschild established his London base, acquiring neighboring land in St James's Place, to the extent that he earned the nickname “Jacob's Place”.

For Jacob, commerce was the path to wealth which he later used to indulge his passion for the arts and philanthropy. This distinguished him from many in the city. Of course, he amassed a large personal fortune, but he also shared his money, whether through the National Gallery, which he presided over, the Courtauld, Somerset House, the Ashmolean… the list goes on. His eyes would shine because he would rather talk about a specific work or the restoration of a building than about the financial results of his companies. But they were there, moving away, getting more funds to reinvest.

While the City had left behind its idiosyncratic style of doing business and that of its fellow takeover merchants (hostile takeovers are virtually unheard of today), Rothschild leaves a gaping void. The arts, for example, have lost a huge and enthusiastic supporter.

It would be truly sad if his passing was marked by the collapse of St James's Place. The current crop should look to his departure for inspiration and ask: what would Jacob have done? And there would be his response.